Recycling Scrap Metal

By Summer Seligmann, C2ST Intern, Loyola University

Recycling can be tricky–it may not always be clear what to put in those blue bins. Although we may have good intentions when we drop our plastics and papers into those bins, the unfortunate reality is that most of this material ends up in a landfill anyway. From January to August of 2021, less than 9% of Chicago’s 578,687 tons put in blue bins were recycled. The city’s low recycling rates stem from a variety of issues in sanitation, but a prominent one is the lack of resources to properly handle large items. Stoves, furnaces, and other household appliances contain metals that can and should be recycled, yet they end up in landfills. Recycling scrap metal can help with this issue, but at what cost?

Scrap metal is metal material recycled from different products; essentially, the leftover metal parts from objects like motors, transformers and faucets. There are two main types: scrap that contains iron (ferrous) and scrap that doesn’t contain iron (nonferrous). Scrap can be brought to a scrap yard where valuable metal material is separated and recycled. It might seem unnecessary to go to a scrap yard when the City of Chicago picks up bulky items for free, but given how low the city’s recycling rates are, there is no guarantee that what is set by the curb will be recycled. Bringing scrap metal directly to a facility reduces what ends up in landfills.

Large appliances, such as washers and dryers, AC units, stoves, and refrigerators contain copper, aluminum, and steel. The initial exploration, extraction, and refining process of these metals can be extremely harmful to the environment. Ore, the minerals from which metals are made, is usually extracted through open-pit mining, a mining technique used when ore is found near the surface of the ground. The changes to the landscape (removal of vegetation, rock, and soil,) and the chemicals left behind, makes open-pit mining one of the most destructive types. Overall, recycling metal is less energy intensive than mining.

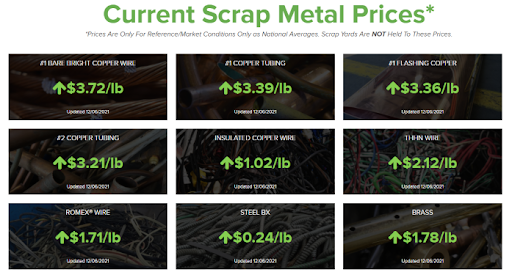

Recycling scrap metal has more in store than just reducing energy consumption and environmental degradation. Scrap yards pay you for the items you bring in, but prices vary by metal and condition (broken down, excess materials removed, etc.). For environmentalists and/or people looking to make some extra cash, you can download different apps that guide users to local scrap yards, give the latest prices for metals, and offer recycling tips. It’s important to note that some appliances (especially older ones) contain refrigerants and possibly other toxic chemicals. These components must be removed before they can be taken to a scrap yard, which requires technician certification for large appliances (the EPA guidelines on how to properly dispose of refrigeration and AC equipment can be accessed here.) Once the refrigerant has been removed, an AC unit can be scrapped because it contains aluminum and copper. Instead of putting the unit out for garbage pick up, it can be brought to a scrap yard where the metal can be properly recycled (which means that ultimately, less energy will be consumed in its reuse) and some extra cash is provided to the person who brought it in. It’s a win-win situation.

Or is it? Recycling scrap metal has its benefits, but there’s a dark side to this industry. There are many regulations set by the EPA that waste sites must follow. One is that landfills are required to have a liner that separates the waste from the ground below. When metal sits in landfills, heavy metals (metallic elements toxic to the living environment) are released, and even with the EPA’s regulations, some pollutants still make it into the soil and groundwater through runoff. Metal in a scrap yard does the same thing. Along with heavy metal, some scrap yards contain metal shredders that flatten vehicles and other objects. Shredders stir up particulate matter (PM), particles made up of different chemicals that are small enough to breathe in, entering the lungs, and sometimes the bloodstream, depending on their size.

Facilities like this are often located in low-income communities, where neighborhoods are treated as dumping grounds. Unfortunately, Chicago is a prime example. There is an ongoing battle over General Iron Industries, a scrap yard that was located in Lincoln Park for decades. Researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago discovered that the shredder at this facility produced lung-damaging levels of PM that traveled downwind in the air. Shortly after this, General Iron announced its plans to move to the Southeast Side of Chicago, a low-income predominantly Latino community. Pollution, noise, and toxic exposure brought by certain scrap yards and waste facilities are bad for all people, but low-income and minority neighborhoods are disproportionately affected. Communities shouldn’t be forced to fight against more pollution when their air, water, and land quality has already suffered from centuries of Chicago’s waste.

With an overall recycling rate currently sitting at 8.28% and 11% as the record high (achieved in 2014), it’s obvious that recycling programs in Chicago aren’t working. Recycling at a scrap yard is a tool that can be used to ensure materials are reused, make some cash in the process, and reduce environmental degradation caused by mining. These facilities, however, can cause great harm to the communities they reside in. Chicago must address its low recycling rates and stop dumping the waste it doesn’t want to handle in low-income communities.