Civilization and its Discontents – 2017

By Sanford (Sandy) Morganstein

There are reasons why we are living in a period witnessing the decline of 17th and 18thCentury Enlightenment values. Reasons why tens of thousands found it necessary to “march for science” and support fact-based reasoning and critical thinking (C2ST – The Enlightening March for Science).

Some of the reasons are easy to understand (I think X will be stronger on Terrorism than Y; I am working two jobs, working too hard and I can’t get ahead — we need a change).

Some of the reasons are harder to understand but that doesn’t mean that today’s issues are new and it doesn’t mean that they haven’t been thought about before.

What do the writings of truly legendary thinkers do to inform our understanding of the rise of instinct and aggressiveness in what we had thought to be a post-bellicose, indeed a fresh humanistic, rational world? Galileo and Darwin made their contributions at great personal risk (C2ST – February and the Birth of Scientific Giants). Albert Einstein importuned Freud to use his psychological insights to enlighten the causes of war and by so doing help prevent it (C2ST – March and the Birth of Another Giant of Science).

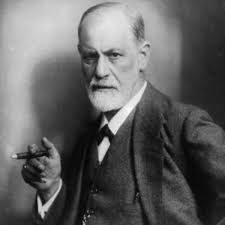

It’s May and May 6 marks the 161st birthday of Sigmund Freud. Let’s take the opportunity to explore Freud’s view on mankind’s tendency to devolve from critical thinking, fact-based reasoning and Freud’s view of rebellion against society’s cultural norms of restraint against our darker selfish impulses.

While there’s a lot about Freud that scientific purists might find objectionable (was the “scientific method” involved in his work?) his insights into the human mind are important to today. Let me just put that part of the discussion aside by quoting from J. F Brown’s 1934 piece entitled “Freud and the Scientific Method” where Brown writes “A similar theme runs through Civilization and its Discontents [Freud’s 1929 book]; if there be any hope for humanity, it lies in the scientific method.”

In Civilization and its Discontents we find the nugget of much of today’s political landscape. Civilization creates laws that place bounds on freedom. So, even when we’re really mad, we can’t kill; when we’re really lusty, we can’t rape; when someone else has a bunch of gold, we can’t steal. In short, Civilization creates inhibitions against our basest, yet human, instincts.

It’s not a new thought; Rousseau addressed many of the same issues in 1762 in a different way in The Social Contract (we forfeit absolute freedom in exchange for the benefits of collective socialization).

In Civilization Freud wrote:

The desire for freedom that makes itself felt in a human community may be a revolt against some existing injustice and so may prove favorable to a further development of civilization and remain compatible with it. But it may also have its origin in the primitive roots of the personality, still unfettered by civilizing influences and become a source of antagonism to culture. Thus the cry for freedom is directed either against particular forms or demands of culture or else against culture itself.

Some of the most relevant of Freud’s insights with respect to the decline of rationality in some of today’s discourse come from the letters between Albert Einstein and Freud written in 1931-1932. The gist of those letters was Einstein’s beckoning to Freud to shed light on the rumbles of war in 1930s Europe. But the wisdom extends beyond war and sheds light on humanity’s proclivity to forgo truth and reality in our discourse.

And this tension rings so true today: Big Government, social safety nets vs small government relaxation of consumer and civil rights protections.

Freud concludes Civilization and its Discontents with the following:

The fateful question of the human species seems to me to be whether and to what extent the cultural process developed in it will succeed in mastering the derangements of communal life …”

Scientists/technologists have a role (obligation?) in mastering those derangements.