Why Are Tornadoes So Unpredictable?

By Summer Seligmann, C2ST Intern, Loyola University

Last month, the all too familiar scenes of uprooted trees, flipped cars, and wrecked homes played out in the southern states. Over 10 tornadoes touched down in Texas in a single day, damaging thousands of homes before the storm headed to Louisiana and Mississippi.

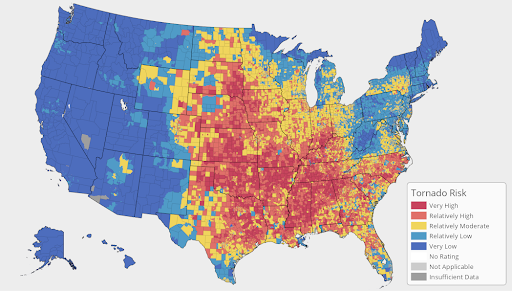

On average, 1,200 tornadoes hit the United States each year. Even though tornadoes are somewhat frequent events, meteorologists have a hard time predicting them.

The average warning time for a tornado is about 13 minutes (as of 2011). In recent years, the warning time window has shrunk, coming in at eight to ten minutes. This limited time frame makes it extremely difficult to prepare for tornadoes. Along with this, more than half of tornado warnings are false alarms. So, it’s hard to know what’s coming: will it be a severe tornado or a standard thunderstorm?

To better predict tornadoes, atmospheric scientists need more data, which means they need to study more tornadoes. The problem is that tornadoes often come and go without allowing adequate time for scientists to document the conditions on the ground.

To better grasp the challenges that come with predicting and preparing for tornadoes, we need to understand the mechanics of this meteorological event. Tornadoes are created from the energy released in a thunderstorm. In most cases, tornadoes come from supercell thunderstorms, an intense type of thunderstorm with a strong rotating updraft (a mesocyclone). Sometimes the atmosphere creates perfect conditions for supercells: if there’s substantial moisture in the air, changes in wind speed and direction, and atmospheric instability, a supercell is born. When meteorologists look at supercell thunderstorms on the radar, they can’t always predict which one will cause a tornado; two thunderstorms might look the same, yet one will create a tornado and the other won’t. Doppler radar detects the circulation in thunderstorms associated with tornadoes, but since there is uncertainty on which supercells produce tornadoes, storm spotters on the ground are needed to verify if a tornado has formed.

Meteorologists might not understand everything about tornadoes, but the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is working to fill in the gaps. This winter, NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL) launched a project called PERiLS (Propogration, Evolution, and Rotation in Linear Storms). PERiLS is a severe storm field campaign that will help atmospheric scientists learn more about tornadoes and other storms. In late winter and spring of 2022 and 2023, instruments will be used to track storms and monitor their patterns in the Southeast United States. This project will allow researchers to study tornadoes’ rapid development with mobile radars, lightning mappers, and trailers, among other tools. Researchers hope that studying the characteristics of tornadoes on the ground will help us predict and prepare for storms in the future.