HeLa Cells: The Immortal Cell Line

By Summer Seligmann, C2ST Intern, Loyola University

The polio vaccine, HPV vaccine, and in vitro fertilization may sound familiar to many, but do you know where each of these breakthroughs came from? Each one of these incredible medical advances was discovered with the help of a tissue sample taken from one woman: Henrietta Lacks.

Henrietta Lacks was diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1951 at The John Hopkins Hospital, in Baltimore. While receiving treatment, Dr. Howard Jones, an American gynecologist, took a sample of her cancerous tissue and sent it to the Gey Tissue Culture Laboratory. Dr. George Gey, the director of the lab, received the cells of all cancer patients at John Hopkins. This practice was standard at the time. Researchers across the country acquired samples from nearby hospitals because they believed that studying tissues would help them understand how cancer affected our bodies. The problem was that the cell cultures (cells grown in a lab from the tissue) couldn’t survive long enough to be studied. Scientists thought that the short survival time of cells was due to the conditions they were grown in. In a quest to make the most sustainable environment for the cells, Dr. Gey decided to use different materials and added antibiotics to reduce the possibility of the cultures getting infected. However, even with the changes Dr. Gey made in his cultivation process, the cells stayed alive for only a short period. This all changed when he received the cells of Henrietta Lacks.

When Lacks’ cells were cultivated, something strange happened; they reproduced at a rate never seen before. Dr. Gey improved the cultivation process, but scientists are still uncertain exactly why the cells of Henrietta Lacks survived in his lab when so many others didn’t. Lacks’ cells later became known as HeLa cells, and the cell line (the cells grown in a lab from the original cell) is still used to this day. HeLa cells are considered “immortal” because they can be grown in a lab indefinitely – they have been dividing for over 60 years. With these cells, scientists have been able to research different viruses, test medications, and develop a method for testing if certain cells are cancerous. And in 1964, HeLa cells were taken into outer space to study how space travel could affect the human body! Most recently, HeLa cells have been used in research to help fight against COVID-19.

Henrietta Lacks’ cells have changed the way we think about modern medicine, but her story isn’t as glorious as it may seem. When Dr. Jones took her cells, he did so without her permission, and after she passed away, her family didn’t know that her cells were being used. Lacks’ case was not an isolated incident; doctors took tissue samples from their patients for years without their consent or knowledge. For most of the twentieth century, there was little discussion about the rights patients had over their bodies. Dr. Jones, Dr. Gey, and researchers who first worked with the HeLa cell line weren’t doing anything illegal because there weren’t laws in place that required patients’ consent. When the story of Lacks’ stolen cells came to light, people started to question if this practice in biomedical research was ethical.

Scientists profited off of Lacks’ cells for years and were careless with her personal information. Her name was mentioned in literature before her family knew her cells were being used. It wasn’t until the 1970s when Lacks’ family found out what was happening. A scientist found that HeLa cells could float in the air (traveling on dust particles) and could contaminate other cell cultures. Unable to tell the contaminated cells from HeLa cells, the scientists called Lacks’ family to get a DNA sample from one of them. Unfortunately, this is the way Henrietta’s husband and family found out that her cells were being used around the world for over 20 years. From 1953 to 1955, there was even a factory at the Tuskegee Institute to mass-produce these cells, with the ability to produce nearly 20,000 cultures a week at its peak. So many people were allowed to access information about Lacks and her family’s DNA, putting them at risk for years, and while they were grieving the loss of Henrietta, scientists made millions.

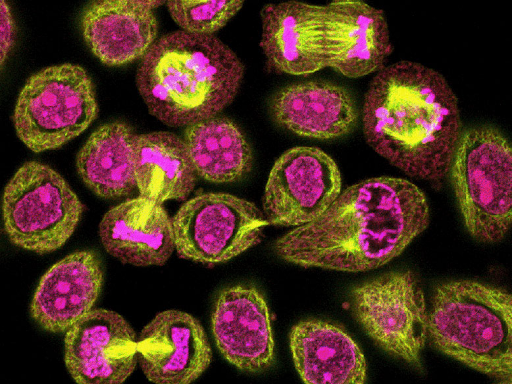

It has been 70 years since Lacks’ passing, and her cells are still used to help people across the globe. Her family has worked with the science community to pass stricter policies on patients’ consent and protection. However, they know more policy changes must come. Until then, her family just wants her to get the recognition she deserves for saving the lives of millions of people. If you would like to see HeLa cells in action, you can watch “Living Human Cells in Culture” here on our website.